‘Writing is like drawing in that it focuses

the mind wonderfully’. –Michael Craig-Martin*

I write these posts in order to understand what I’ve seen or

experienced, better. It is a way of processing, analysing those thoughts for as

much my own record as it may (hopefully) be as of interest to anyone else that

chooses to read it. The same can be said of drawing and my relationship with it

as a means of focusing the mind allowing the opportunity for new thoughts, or

indeed the almost meditative expulsion of having no thoughts at all (both as

equally valuable). Having a passion for

both, with that in mind, I began writing this post about ‘Great British

Drawings’ exhibition of over 100 drawings by artists such as, Gainsborough,

Turner, Rossetti, Millais, Holman Hunt, David Hockney, Gwen John, Walter

Sickert, Ravilious, Edward Lear, William Blake, Samuel Palmer and Tom Phillips

at the Ashmolean in Oxford.

|

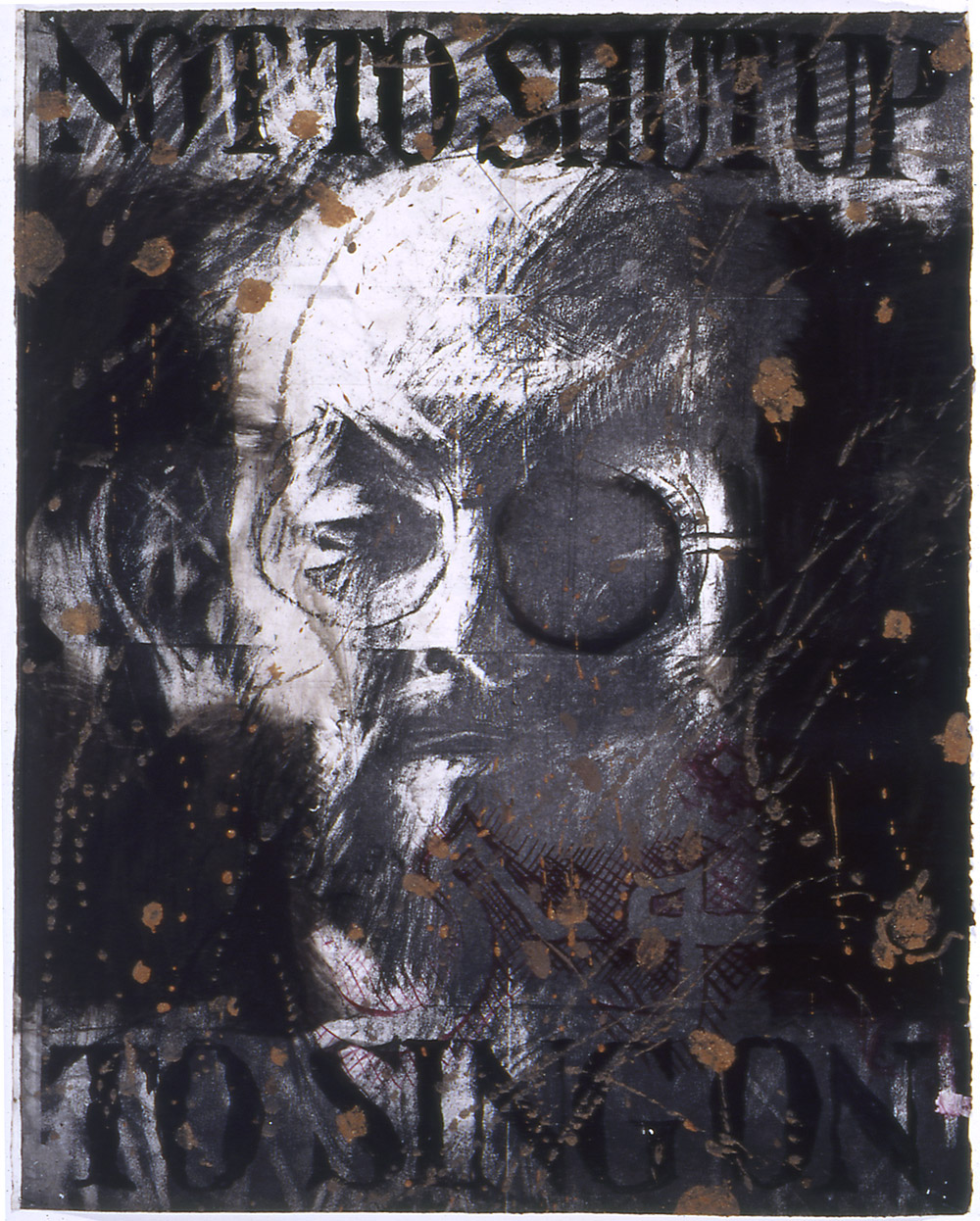

| Tom Phillips 'Salman Rushdie' (probably 1993) Charcoal, red and black body colours, brown mud bound in liquitex mat medium on white paper. |

Most exhibitions I visit are intentional, in the sense that

I plan to go see them. Visiting ‘Great British Drawings’ was more fortuitous in

that I went to see it simply because I had some time to spare! In that respect it was a pleasant surprise

with equally a few seldom-seen gems amongst the collection on display. These

include a Tom Phillips charcoal, mud and liquitex drawing of Salman Rushdie,

(pictured above) which was uncannily Jim Dine like in its drawing style through heavy

use of black and intense mark-making. Elsewhere it was refreshing to see a pen

and ink drawing by Edward Coley Burne-Jones (of Pre-Raphaelite fame) that was

in its small, more intimate scale more engaging and visually interesting in

tone/marks than any of his paintings in my opinion. A few more of the

Pre-Raphaelite ‘gang’ had work displayed in this exhibition and whilst I

wouldn’t say I’m a fan of work from that period the difference in a perceived sense

of warmth between their drawings and their paintings was quite striking. It

reaffirmed that the pre-emptive nature of drawing, in the way it was used often

before or as a way of composing a painting is so much more revealing of the

artists hand and first impression of what they are looking at often than the

painting. The painting is more measured in that it has been considered, edited

and planned to convey what the artist ‘wants you to see’ whereas a drawing can

be as considered but is often more ‘of the moment’ and sort-of as consequence,

I feel, slightly more real (‘real’ in the integrity sense of the word rather

than necessarily ‘realistic’) Turner is however a good exception to this theory

whose drawings are also in this exhibition, he paints very much how he draws

and the drawings inform the painting as much as the drawing is informed by the

materials he is using. Again, it was

great to see these smaller on paper watercolours which if anything felt

slightly fresher and less laboured than some of his paintings.

|

| Samuel Palmer 'The valley with a bright cloud' (1825) Pen and dark brown ink with sepia mixed with gum Arabic, varnished. |

|

| Edward Lear 'Contstantinople from Eyoub' (1848) Pen and brown ink with watercolour over graphite on wove paper. |

Flavour of the month, Eric Ravilious also had a drawing

present in this exhibition along with Samuel Palmer (pictured above) who feels

vaguely similar in that both were attempting to depict the romanticism of the

English landscape, the undulating hills, cloudy skies, ploughed furrows in

fields, rows of corn, hidden pathways, stone walls and all the variety in

textures of trees, leaves, hedges and fauna. I also admired the draughtsmanship

of artists such as Edward Lear whose illustrations I was familiar with but

until now had never seen these more technical drawings (pictured above) which although

preparatory for something finished are still quite elegantly sensitive and

informative in their own right. There

was also work that reminded me of the importance of drawing as capturing an

impression of something and the immediacy and observational sketchiness of John

Sell Cotman’s ‘A Ruined House’ (pictured below) being one example and also a more

unusual contrast to the familiar subject matter predominantly limited to classical

architecture or castles (though many of these perhaps also united to this

drawing in being ruins but of a slightly different nature).

|

| John Sell Cotman 'A Runined House' (1807) Watercolour over graphite on paper. |

This was a quietly contemplative exhibition, with lots of

looking and noticing attention to detail of the kind which drawing tends to

invite more gently than painting so whilst the Ashmolean probably possess infinitely

more work they could have possibly shown in the space it still felt as though

there was a lot to see. Certainly a lot to think about.

‘Great British

Drawings’ is on at the Ashmolean, Oxford until August 31st.

*Taken from CRAIG-MARTIN, M; ‘On being an

artist’ (2015) Art Books Publishing: London. p8.

*Images from: http://www.tomphillips.co.uk; http://lowres-picturecabinet.com; http://www.myartprints.com

No comments:

Post a Comment