The stage is set as eighty-nine countries across the

world present their pavilions from the 9th May until 22nd

November in the 56th Venice Biennale. This year’s central exhibition

has been curated by Okwui Enwezor, titled ‘All the World’s Futures’ and at its core features live performances and

underpinning ideas expressed in Karl Marx’s ‘Das Kapital’. The future doesn’t

come across too brightly in this Biennale and as consequence has already drawn

criticism for being highly political, sombre and ‘more depressing’ than in

previous years. ‘All the World’s Futures’ is however, ambitious and enables for

a broad capacity of works like its preceding Biennale theme, ‘The Encyclopaedic

Palace’ whose title covered pretty much anything! I am reminded of when I was a

child and creating an imaginary ‘everything in the world backpack’ which

travelled with me on all my childhood adventures as well as frequently

appearing in my written stories. It was a way of encompassing everything one

could ever need as well as a sort-of lazy alternative to having to imagine

something specific- rather a means of imagination subject to necessity, if I

needed a ladder, saucepan, compass or rowing boat in the course of play,

anything one could possibly ever need would undoubtedly be covered by the

‘everything in the world backpack’. The 56th Venice Biennale feels a

little the same, in its efforts to cover the all encompassing breadth of

existence from human endeavour to the social, political, environmental,

symbolic and aesthetic. So much so that if you were to wonder, ‘is there any

work here featuring string?’ you’ll undoubtedly find it –everything from bones,

tyres, shops, keys, bread, earth, trees, glass, flags, fabric, instruments,

boats, video games, immersive installation, sound, chalkboards, ready-mades,

recycling, text, neon, driftwood, conflict, film, opera, war, eating,

sexuality, identity, the sea, archiving, minimalism, technology, stone, metal,

newspapers, fans, walls, doors, suitcases , history, people, paint, place is

represented making it an almost impossible task to surmise just what isn’t

included either conceptually or in material! Does it fall flat of being too

disorganised, too crowded? Or is it too specific in being overtly political or

depressing as the reviews seem to claim? I am less sure of the latter as it

moderately depends on what glasses you are wearing when viewing the work as I

certainly found there to be enough variety, curiosity and

uplifiting/depressing/confusing wonderment to fill a lifetimes worth of

futures.

Over the course of three sizzling Venetian days I

attempted to visually munch my way through as much of the Biennale as possible

across its two main venues (the Giardini and Arsenale) and around the city so I

can present what is hopefully a digested view of some of the highlights of this

year’s Venice Biennale 2015! Burp!

Top Five Biennale Pavilions (in no particular order)

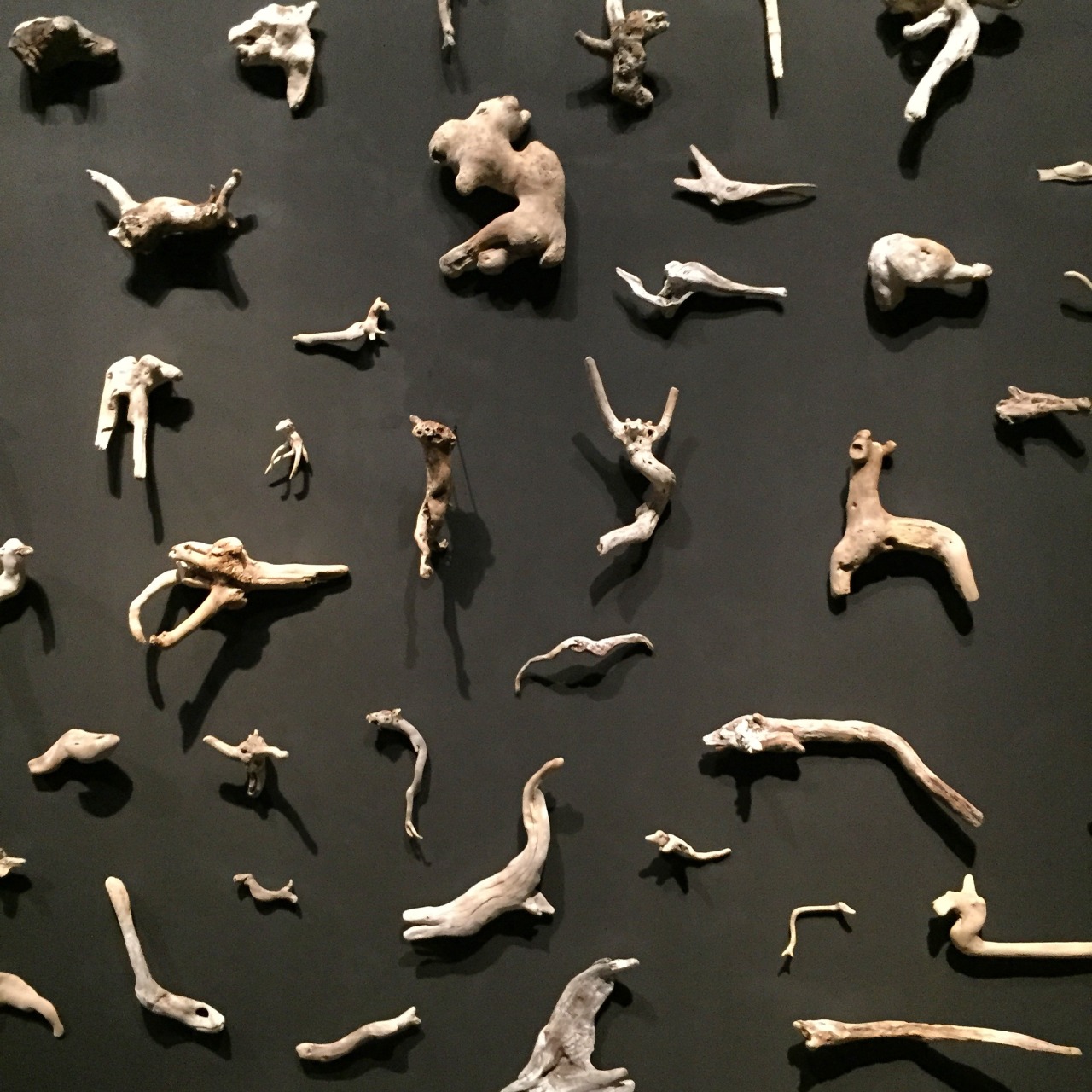

Netherlands – herman de vries ‘to be always to be’ How could you make reference to ‘Das Kaptial’ without

having plenty of tools scattered throughout? This year’s Biennale certainly had

more than I recall seeing last year which is never a bad thing! The Netherlands

pavilion was no exception and as one of the first I visited, was a delight to

see dozens of sickles laid out on the floor so that each of their shapes is

emphasised highlighting their similarities yet their differences at the same

time. This was one piece in the body of work by herman de vries whose

contribution to the Netherlands pavilion took the form of a series of

natural/earth-based works that are experienced by the eye, ear, body and nose.

Leaves, shells, plants, soil, stones, flowers are collected, isolated and

displayed drawing attention to the oneness and diversity of the world

surrounding us. The sickles create an association between the tool as an

extension of the body and mediator to the crops and land in which it comes into

contact with. Aside from my obvious bias in this pavilion featuring tools, I

found the compartmentalisation of each of the elements, soil, stone, plant,

tool etc. to be immensely satisfying which may stem from my interest in

typology of tools and tool catalogues. Aesthetically there is something

pleasing about the order of grids/isolating objects in this way as well as the

psychological implications of grouping/collecting things to form a bigger sense

of control or unity even more interesting when done so with natural objects

like plants/leaves which by their very nature defy the man-made perception of

order and control. It was a very gentle exhibition and not fascinating because

it was necessarily anything new, but was more reassuring as it confirmed what

I’ve seen so many people do (both artists and non alike) using natural

materials and a connection with documenting, noticing, looking at natural

world. It also underlines a very basic belief that an appreciation of

understanding, engaging in the world around us begins with noticing it.

Netherlands – herman de vries ‘to be always to be’ How could you make reference to ‘Das Kaptial’ without

having plenty of tools scattered throughout? This year’s Biennale certainly had

more than I recall seeing last year which is never a bad thing! The Netherlands

pavilion was no exception and as one of the first I visited, was a delight to

see dozens of sickles laid out on the floor so that each of their shapes is

emphasised highlighting their similarities yet their differences at the same

time. This was one piece in the body of work by herman de vries whose

contribution to the Netherlands pavilion took the form of a series of

natural/earth-based works that are experienced by the eye, ear, body and nose.

Leaves, shells, plants, soil, stones, flowers are collected, isolated and

displayed drawing attention to the oneness and diversity of the world

surrounding us. The sickles create an association between the tool as an

extension of the body and mediator to the crops and land in which it comes into

contact with. Aside from my obvious bias in this pavilion featuring tools, I

found the compartmentalisation of each of the elements, soil, stone, plant,

tool etc. to be immensely satisfying which may stem from my interest in

typology of tools and tool catalogues. Aesthetically there is something

pleasing about the order of grids/isolating objects in this way as well as the

psychological implications of grouping/collecting things to form a bigger sense

of control or unity even more interesting when done so with natural objects

like plants/leaves which by their very nature defy the man-made perception of

order and control. It was a very gentle exhibition and not fascinating because

it was necessarily anything new, but was more reassuring as it confirmed what

I’ve seen so many people do (both artists and non alike) using natural

materials and a connection with documenting, noticing, looking at natural

world. It also underlines a very basic belief that an appreciation of

understanding, engaging in the world around us begins with noticing it.

Israel –Tsibi Geva ‘Archaeology of the Present’

Hundreds of disused car tyres encase the outside of the

Israeli pavilion whilst inside window panels and shutters line the walls.

Perceptions of inside, outside the functional and the representational are

manipulated creating new assemblages, installations and sculptures that in some

cases block or create a sense of sometimes confrontational discomfort for the

viewer. In complete contrast to the natural tone of the Netherlands, Israel

presents an altogether urban, industrialised pavilion of bicycles, ladders,

weapons, metal girders, wire, and wood. Not

so much an environmental or recycling statement as a formal, aesthetic one

where wheels become circles, ladders –lines, fencing –grids and street signs –squares.

Together their formal qualities and crudeness create interesting compositions,

tones, surfaces, imagery and spatial ambiguity. Echoes of the Bauhaus,

Rauschenberg and Johns alongside what could only be described as Israel’s

version of a Tapies would suggest that whilst Israel isn’t bringing much

originality to proceedings but non-the-less it is an aesthetic I am glad is

still being explored and utilised as made manifest in this pavilion.

The BGL artists collective comprising of three Canadian

artists present the visually glorious and great fun, ‘Canadassimo’ installation

raising issues related to economics and the art system centred around the

notion of ‘unproductivity’. Humorously, they attempt to do so with a three part

installation set as a shop, living space and studio the latter of which

couldn’t be any more extravagant and in its sheer abundance of paint cans,

shoes, tools, palettes and other artistic paraphernalia appears in some ways

the complete opposite of unproductivity. However the point being that out of

all this paint, all these brushes and all of this mess no actual ‘art work’ has

been produced. There is a huge sense of artificiality in this work from the

kitsch colours to the fact that it has been staged to look as though work has

taken place when in a way it hasn’t. We do not see the product of all these

half empty paint cans, merely the mass of their existence. It is taking the

idea of the consumerist, product-based Westernised nature of being an artist

and exaggerating it to make a point that we are conditioned to buy all of these

things in order to ‘make art’ when these objects often sit taking up space

inadvertently becoming the art themselves. The whole thing is very visually

pleasing so much so I am sceptical that I really whole-heartedly ‘believe’ in

it as a piece of work that will resonate with me for years to come. Is it a bit

of a one-liner and does it really offer anything new in how I think about the

system of ‘what it means to make art’? Certainly in the short-term it is a

joyous thing that will quietly rekindle that simple pleasure of painting

without a cause and that’s never a bad thing.

Poland –C.T Jasper and Joanna Malinowska ‘Halka/Haiti 18°48’05”N

72°23’01”W’

What do you get if you take the principle idea behind Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, a Polish Opera and Saint-Domingue in Haiti? Answer the Polish Pavilion video installation which takes Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, a mad/romantic anti-hero who attempts through all manner of frustrating human endurance build an opera house in the Amazon. Sharing a motivation in the faith of the universal power of opera C.T Jasper and Malinowska attempt to similarly bring opera to the island whilst remaining ‘not uncritical to the aspect of cultural colonization’. The result is a large ‘in the round’ video projection of a performance of the Polish opera ‘Halka’ in Saint-Domingue uniting a Polish opera with the land in which Polish soldiers fought to defend its independence during 1802. I have to admit part of my enjoyment of this piece comes from having seen Fitzcarraldo and similarly, like many artists I expect, relating to the idea of perseverance in the face of adversity for the motivation of a love of the arts. In the film the impossible struggle to make this dream a reality doesn’t bare fruition so taking that idea and enabling it to happen, in the very modern way of not being restricted by having a theatre in which to perform in, Fitzcarraldo’s dream is made into reality. It is not done with an arrogance that the Westernised version of opera is necessarily better or what is needed for a place like Haiti but speaks more of the universal language of music and storytelling across two different cultures in which we as the viewer are watching both the performance and audience at the same time. I actually found myself watching the reactions of the audience and movements of the children, animals and passersby more than the performance itself.

What do you get if you take the principle idea behind Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, a Polish Opera and Saint-Domingue in Haiti? Answer the Polish Pavilion video installation which takes Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, a mad/romantic anti-hero who attempts through all manner of frustrating human endurance build an opera house in the Amazon. Sharing a motivation in the faith of the universal power of opera C.T Jasper and Malinowska attempt to similarly bring opera to the island whilst remaining ‘not uncritical to the aspect of cultural colonization’. The result is a large ‘in the round’ video projection of a performance of the Polish opera ‘Halka’ in Saint-Domingue uniting a Polish opera with the land in which Polish soldiers fought to defend its independence during 1802. I have to admit part of my enjoyment of this piece comes from having seen Fitzcarraldo and similarly, like many artists I expect, relating to the idea of perseverance in the face of adversity for the motivation of a love of the arts. In the film the impossible struggle to make this dream a reality doesn’t bare fruition so taking that idea and enabling it to happen, in the very modern way of not being restricted by having a theatre in which to perform in, Fitzcarraldo’s dream is made into reality. It is not done with an arrogance that the Westernised version of opera is necessarily better or what is needed for a place like Haiti but speaks more of the universal language of music and storytelling across two different cultures in which we as the viewer are watching both the performance and audience at the same time. I actually found myself watching the reactions of the audience and movements of the children, animals and passersby more than the performance itself.

Romania –Adrian Ghenie ‘Darwin’s Room’ First spotted in the 2008 Liverpool Biennial, I would cautiously go as far to say that Adrian Ghenie is one of the best painters in this year’s Biennale even though, sadly there aren’t many to choose from (Marlene Dumas coming in at a close second). Titled ‘Drawin’s Room’ the Romanian pavilion features three rooms of Ghenie’s paintings and a few of his drawings, the majority of which are portraits of Charles Darwin throughout various ages of his life. Purely from a painterly view, these are really voluptuously painted portraits which share a darkly, distorted layering and manipulation of paint on canvas as though it were a fleshy surface. They remind me of more thickly painted and colourful Francis Bacon’s but sharing some of their flatness so as not to become as thick as an Auerbach. What they offer in terms of a perspective into Charles Darwin, his work and or ideas feels significantly less. I often think portraits of figures such as Darwin, Einstein, Freud etc. don’t really work as portraits as such, as the people they depict, apart from being dead are so iconic and recognisable we don’t really see them as people anymore, but more as a symbol of their ideas/discoveries. Hence, when I look at Ghenie’s paintings of Darwin, I either think; in their distortion they are so unrecognisable that it could be any face, any person; or, I recognise it as being Darwin and so begin to look for things in the painting which allude to ideas of evolution. If anything in distorting historical figures in Ghenie’s paintings is perhaps an attempt to convey the true nature of these people and not the myth. In the Darwin portraits I think they speak more of the subconscious than the scientific and it is perhaps that juxtaposition what makes it interesting.

Romania –Adrian Ghenie ‘Darwin’s Room’ First spotted in the 2008 Liverpool Biennial, I would cautiously go as far to say that Adrian Ghenie is one of the best painters in this year’s Biennale even though, sadly there aren’t many to choose from (Marlene Dumas coming in at a close second). Titled ‘Drawin’s Room’ the Romanian pavilion features three rooms of Ghenie’s paintings and a few of his drawings, the majority of which are portraits of Charles Darwin throughout various ages of his life. Purely from a painterly view, these are really voluptuously painted portraits which share a darkly, distorted layering and manipulation of paint on canvas as though it were a fleshy surface. They remind me of more thickly painted and colourful Francis Bacon’s but sharing some of their flatness so as not to become as thick as an Auerbach. What they offer in terms of a perspective into Charles Darwin, his work and or ideas feels significantly less. I often think portraits of figures such as Darwin, Einstein, Freud etc. don’t really work as portraits as such, as the people they depict, apart from being dead are so iconic and recognisable we don’t really see them as people anymore, but more as a symbol of their ideas/discoveries. Hence, when I look at Ghenie’s paintings of Darwin, I either think; in their distortion they are so unrecognisable that it could be any face, any person; or, I recognise it as being Darwin and so begin to look for things in the painting which allude to ideas of evolution. If anything in distorting historical figures in Ghenie’s paintings is perhaps an attempt to convey the true nature of these people and not the myth. In the Darwin portraits I think they speak more of the subconscious than the scientific and it is perhaps that juxtaposition what makes it interesting.

Other highlights:

|

|

Melvin Edwards Wonderfully intricate, complex sculptures to draw comprising of welded together scraps and parts (yes, including tools!). |

Was this year’s Biennale original or innovative enough

overall? I think so. I think there is far greater emphasis on film and digital

technologies this time around, with even less painting which led me to feeling

as though the previous years left more to the imagination. At times in this

year’s Biennale there were so many films it would be in fact impossible over

the time limit of two days to watch each one in their entirety which is where

the distinction between good and outstanding film makers really becomes important,

with artists like John Akomfrah, Steve McQueen, Chantal Akerman, Mika

Rottenberg (reminiscent of Matthew Barney/David Lynch) and Peter Greenaway (who

has a massive video installation in the Italian Pavilion) standing out amongst the bunch. In

the central exhibition it is true that there were more swords, weapons, flags

and skulls than perhaps ever before which is understandable reasoning for the

Biennale being more political, war torn, morbid and sombre this year, but then

this was always counter balanced by the media-friendly and perfectly pleasing

works of the likes of the red threaded keys of Japan and the mechanised moving

trees of the French pavilion so the whole thing is too complex

to make a fair overall assessment. In Enwezor’s view the aim of this year’s

Biennale was to ‘Bring together publics in acts of looking listening,

responding, engaging and speaking in order to make sense of the current

upheaval’. The world may have become a little darker in recent years, but

whether the presence of swords, canons and broken window panes really reflects

a bleak world view of future dystopias is more a matter of perspective than

prophecy. The Biennale’s greatest asset is also its biggest burden that in

being so big and diverse it suffers from the loss of an overall sense of

coherence, message or understanding though it remains a terrible, bordering on

gluttonous, binge of the best and worst of the art world and for that alone

makes it worth celebrating. For a breath of fresh air the Punta Della Dogana

exhibition ‘Slip of the Tongue’ curated and featuring work from Denmark’s Danh

Vo offers a welcome rest bite to the cramming of work and space of the Venice

Biennale, but more on that next time...

Yum, yum, yum! Please art binge responsibly.

The 56th Venice Biennale, ‘All the World’s

Futures’ runs until November 22nd 2015. More details found at:

Images marked with a (*)

sourced from:

No comments:

Post a Comment