“Perhaps the most shocking tactic that’s left to artists

these days is sincerity.” –Grayson Perry

A year ago on October 15th I tuned in to Radio

4 for the first time. Make of that what you will, but to my young ears even the

thought of listening to anything other than music on the radio (even with the annoying

adverts) seemed like a waste of airwaves. Fortunately, such is my commitment to

art and attempting to understand it better that I was willing to change

stations that day to listen to a Turner Prize winning transvestite potter (as

he calls himself) speculate for an hour

on the age old debate of ‘what is art’ amongst other things. How wrong I was

not to tune into Radio 4 until then, I’m so glad I did and I’m sure that if

Grayson Perry knew (or even cared) that I was adjusting my preset music channels

on my radio to listen to him discuss the subject of taste in art, would be

slightly amused (or perhaps horrified) by the irony of my decision.

At the time when I listened to these weekly, four-part

lectures (known as the Reith Lectures) I felt quite productively riled by it all,

it felt more like a manifesto, a ‘call to arms’ than a lecture. I was strongly

in agreement with many of his views, from the intimidating nature of commercial

galleries, self consciousness in making art, the difficulty of irony and

conflict between seriousness and amateur in art, to how anti-establishment loses

its edge when it becomes popular. It was as though he had so entertainingly and

eloquently voiced many of the opinions and thoughts I’d contemplated or more

often heard voiced by my friends and peers (artists and non artists alike). And like many I spoke to at the

time, I identified with his delivery of plain speaking, honest observation, wit

and impassioned rhetoric. So much so, that I made copious notes on it all with

lots of circling and heavy underlining of things which really struck-a-chord or

had resonance. There were a lot! I never published these thoughts into a post,

until now, probably because at the time it was so popular I felt I’d only be

regurgitating what everyone already felt and knew.

Nearly a year later and the riling and irony continues as

I’ve retreated to the confines of my room to escape the tawdry blare of the X

Factor to read the newly published book, ‘Playing to the Gallery’ which is

almost word-for-word a transcript of the Reith Lectures Perry gave last year. I

have no problem in knowing which I prefer, which I undoubtedly enjoy the most

and which I think is a steaming pile of trash, but paradoxically, as Perry in

the opening chapter of the book mentions, there are problems in knowing what is good taste and which is bad. Is taste purely subjective? Where do

ideas of quality and authenticity sit when deciding a work’s value? Perry

argues that in the same way beauty can be determined by a familiarity of reinforced ideas, is similar to how we assert and measure taste with popularity,

or in other words, the myth of ‘if it’s popular it must be good’. However, as

he also acknowledges, popularity and the arts don’t necessarily go hand-in-hand

with some artists choosing to reject the idea altogether. What is in agreement

is that there is a certain set of criteria or ‘boundaries’ as Perry names them

which determine whether a work of art is a work of art, although this in-turn

depends on the right people saying or deciding it is....it all gets a bit woolly;

and if we are to start judging whether the X Factor is good or poor taste then

we might as well start asking is the X Factor art?

“ ‘We’re all bohemians now’. And if you think about it, all the things

that were once seen as subversive and dangerous like tattoos and piercings and

drugs and interracial sex and fetishism and other-ness –they crop up on X

Factor now on a Saturday night for family viewing.

As a creative person/artist (albeit someone who has

studied it and now remains drifting, a wandering purveyor on the outskirts of

the world that is art) much of Perry’s discussion is preaching to the converted but

offers a refreshingly honest critique of the art world, its challenges and its pitfalls; advice in tenacity and commitment, for both aspiring, ‘emerging’

and practicing artists alike.

“As an artist the ability to resist peer pressure, to trust one’s own

judgement, is vital, but it can be a lonely and anxiety-inducing procedure.”

And on the subject of angst, there’s a lot of it in this

book, which is probably why I related to it so much, Perry addresses the angst felt

in viewing and creating art, in particular how difficult it is to remain un-cynical

when, he argues, the legacy of art history has already covered so many acts of rebellion,

discovery, shock and protest that it leaves current generates of artists

without a ‘cause’...what is art if it is no longer about storytelling, mass communication

or pushing boundaries? And is that in itself something to make art about?

“Because of course art’s primary role is not an asset class and it’s

not necessarily about being an urban-regeneration catalyst, Its most important

role is to make meaning.”

This is one of those art books that will probably

end up on a first year reading list on Fine Art degree courses, like ‘Ways of

seeing’ by Berger or ‘But is it art?’ by Cynthia Freeland. Rightly so, it covers much in the way of art history by

offering how it has affected or how we can interpret contemporary art today.

However all of these books are very much starting points to these wider debates

and Perry is particularly good at provoking in an informed way but slightly holds back from being the academic that he is probably through fear of alienating people.

If anything it points to the fact that educating people

about art is essential to both its survival and future development, which isn’t

necessarily about making more artists but equipping people, even the most tentative

art gallery tourist with the confidence to question and talk about art. True

you can still experience art without having any education on the subject, but I

think that experience is all the richer and more rewarding when there is some understanding

of why, when and how a work was created. That’s not the same as saying people

should be comfortable around art, it usually works best when it’s the opposite,

but should be about encouraging people that if they think, look, experience or

talk about art then they will be rewarded with alternative world views, new

perspectives on things or ways of seeing. I still find looking and

understanding a lot of art incredibly difficult, but the difference is that I’ve

learnt how to enjoy that challenge and have subjected myself to as much as I can so I am familiar with how to go about trying to understand it if I

want to. This may have also come at a cost of becoming increasingly sceptical and cynical about a lot of art, but it is all the more exciting when I find something that unsettles that perspective. Art is a challenge and a

question and as Perry acknowledges, needs people to keep questioning it and the

subjects it deals with.

In some ways in Perry's initial resisting the arts

establishment only to have now become part of it derives from his own experiences

and so I wonder if his central polemic of, ‘anyone can enjoy art’ and explanations

for doing so is lost if the audience that would have most to gain from hearing this

message is also the least likely audience to be reading a book on art. At least

through his determined, angst ridden acceptance into the art world, Perry has become

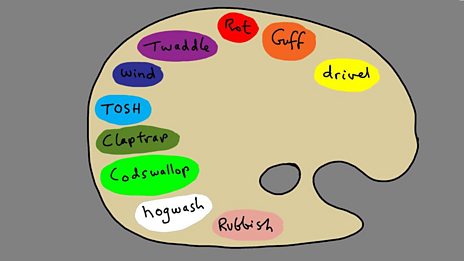

more widely known, dare I say, more ‘popular’ and in being broadcast on Radio 4

reached a wider audience than what it would have in book format alone? Clearly even more if it had been aired on the X factor! Although I often wonder if everyone accepted and understood art then would it still be art? Or would it somehow loose its mystery or its pompousness and in its familiarity become dull or breed contempt? Maybe art's greatest asset, its key to longevity is the search to understanding it...?Instead of trying to make sense of it all I suppose I should try to embrace art in its many contradictions, challenges and on-going changes as they're the reasons I still want to find out more. An extra addition to the book is that it contains several amusing cartoons drawn by Perry that dryly illustrate some of the opinions in the book, but above all it reads like any good lecture should, it informs you, it provokes you, it amuses you and ultimately it lifts you,

"At this point I may risk a dark sincerity. I feel it is a noble thing to be an artist. You're a pilgrim on the road to meaning."

My own dark sincerity is that despite how good it was I haven't listened to Radio 4 since, but I have continued to make and see a whole lot of art.