If M C Escher could have made a video game app it might have

looked something like this...

It seems reasonable to assume that if weathered painted

wooden doors, rusty tins and all manner of broken detritus can be art; (as well

as films, music and certain branches of cookery, gardening and sport which can

also be seen as art forms) then surely some aspects of videogames should also

be recognised as such? And does it really matter if they are/aren’t? I’m not going

any further to attempt tackling the age old debate of what ‘is’ and ‘isn’t’

art, numerous philosophers, writers and thinkers have attempted to do so

infinitely better than me with the only certainty is that we’re still not quite sure and that it is ever changing. It is ‘an excessively broad church’ I was once

told. Hence, given the amount of

production, imagination, people and time invested in developing games, fuelled by the money

the industry generates in Britain alone each year (in excess of 3.5 billion!)

it is slightly surprising that videogames are met with a degree of resistance

and snobbery in being perceived, critiqued or categorised under the ‘art

umbrella’.

I’m all for a bit of inclusivity having played video

games as I have watched movies, listened to music and dabbled in art (in the

conventional sense) for years. When I completely per chance came across an

online downloadable app called ‘Monument Valley’, a game that looked and played

like being in an M C Escher painting I thought it was long overdue that I hit

the keys and articulated my thoughts here on the blog. [That and to prove that there is more to

videogames as art than the likes of David Hockney drawing a few digital

paintings on an ipad.]

In ‘Monument Valley’ the concept is a simple one; move the

protagonist ‘girl in a pointy hat’ from A to point B via navigating your way

through the ‘impossible’ architecture of a topsy-turvey citadel of

er...monuments. Combining puzzle solving with narrative the player embarks on a

series of challenges in which they control parts of the structures to create

new routes and walkways that once didn’t exist in order to progress through the

game. The illusionary perspective, that only really makes sense if/when you

play the game arguably borrows its sense of impossible realism from the likes

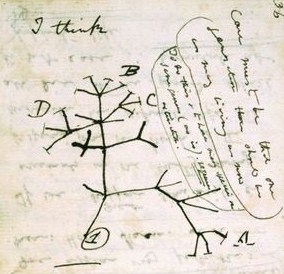

of the Surrealists and artists like M C Escher (see images below). I

don’t want to intentionally make it sound 'dry' by over analysing it, as

ultimately it is a really fun, elegant and beautifully simple looking game, but

one in which (as in many games) has had a great deal of design, craft and

creativity put into it. Surely worth some appreciation at least?

The games creator Ken Wong claimed the design was inspired by Japanese prints and minimalist sculpture. The crisp, cell-shaded design with very sparse, flat and often mist shrouded backgrounds does have a very Japanese quality to it. Equally the music and sound effects in 'Monument Valley' have a Arabic, Eastern sound which alters based on the movements of the buildings when you touch the screen. The overall affect is very thoughtful and well put together gentle and calming game. In terms of where it sits in the bigger gaming community it reminds me of a growing trend for architecture design and utopias in games like Minecraft where vast, intricate and idealised visions of the metropolis or imagined structures can be created. In these virtual world's things can be created that exceed the limitations of reality and could and should be used as start points and spring boards for creativity and design. Who wouldn't want to live in a house like this?

|

| M C Escher 'Ascending and Descending' (1960) Lithographic print |

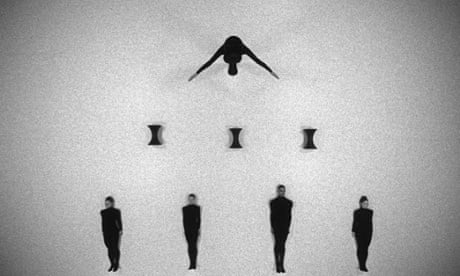

If you’re in need of further convincing then look no further than the De Chirico influenced art style from the 2001 Playstation Game, 'Ico' (see image below) .

|

| (Left) 'Mystery and Melancholy of a Street' (1914) Giorgio de Chirico -- (Right) 'Ico' (2001) Playstation 2 |

Videogames operate on a similar conceptual basis of puzzle solving, communication and engagement that can be not too dissimilar to the process of viewing art. Similarly they are interactive and immersive, games and I quote ‘speak to people’ and communicate in a medium that is debatably more of ‘our time’ than traditional methods of painting, printmaking. Without going into it now, I speculate that the most innovative artists are the ones utilising new technologies such as 3D printing, laser cutting etc. to make work.

In the same way every scene from certain films can be perceived as an individual framed work of art so can shots or scenes from videogames be perceived as such. Increasingly as well videogames are becoming more cinematic in their story telling and realism ('Heavy Rain' from 2010 being one example). Unlike a lot of art however videogames offer the ‘liberation of shared

authorship’ as one Oxford professor** on a lecture on videogames as art described

the process of interacting with games having one author who programmes/creates

the constraints, rules and possibilities but multiple authors in those who

interact with it and in the case of games like, ‘Minecraft’ or ‘Second Life’

contribute creating and altering elements within that digital universe. I

struggled to think of any artists whose work operated in this way, other than

that of participatory art and some environmental art projects. To be continued....

In 2012 the MOMA held an exhibition of iconic videogames

(such as PACMAN and Pong) alongside its collection of Modern art works.

Unsurprisingly it was met with some controversy and sparked much debate as to

whether something which originated as a means of entertainment, play and fun

could really be considered as art with one critic making a case for games not being an art form with the analogy of likening it to chess,

“Chess is a great game, but even the finest chess player

in the world isn't an artist. She is a chess player. Artistry may

have gone into the design if the chess pieces. But the game of chess

itself is not art nor does it generate art – it is just a game.”

Still if that is the case then we are ignoring the fact

that ‘everyone’s favourite’ art protagonist, Marcel Duchamp had not only opened

the doors to allowing ‘anything’ to be considered as art he specifically

recognised along with Manray that chess too could be art and shared many of its

traits with the process of making it,

‘...they saw qualities in it that they thought essential

to their art –opportunities for improvisiation and play based upon skill, not

chance; ritualised forms and iconography that embodied the violence and eroticism

of the world around them; a new type of artist-viewer relationship; a unique

sense of spatial organisation; and a set of contradictions that could be

transposed to aesthetic or anti-aesthetic ends.’*

The danger of inclusivity or ‘if everything can be art’

can mean that you dilute the distinction of what ‘Fine Art’ may be, but it’s

not to say that all video games are art or in the same way that all videogames

aren’t necessarily ‘good’ art. Although with more and more time people are

spending online, in virtual worlds and the accessibility online generally it is

a debate that is going to become increasingly hard for its critics to ignore. Videogames

continue to develop that exceed their original origins of being merely things of 'play' and indeed on the other hand are one of the few mediums which truly value the role of play as a means of discovery and learning.

With a Minecraft exhibition featuring 3D reproductions of famous Modernist paintings currently on show at the Tate it seems that computing technology and in particular videogames are in fact being used as a means of appealing to a younger generation. I'd argue that it is more than a gimmicky passing fad and like it or loathe it, it seems they are around to stay. Popularity isn’t necessarily a conclusive

bench mark for whether something can be considered as art or not, but the

increased popularity of gaming and game production is worthy of our attention. Only

time will tell.

Similar links and references:

*LIST, L. (2008) Chess

as Art, In: MUNDY, J. (2008) Duchamp, Manray, Picabia, London: Tate

Publishing . pp. 133-143

.png)

.png)