If you are lucky enough to visit ‘Slip of the Tongue’ at

Punta Della Dogana in Venice this year there will be some points during your

viewing where you will look possibly at a stone axe head sticking out the top

of a block of clay and question ‘what does this all mean?!’ ‘uh....’

That’s right! This post marks the glorious return of ‘the

bit pretentious one’ art gallery, Punta Della Dogana, Venice. Hard to believe

it was almost two years since my last visit during the 2013 Biennale when I

initially dubbed the contemporary art gallery as the ‘more pretentious’ of its

Venetian counterparts [see http://spannerintheworkz.blogspot.co.uk/2013/12/the-bit-pretentious-one.html].

June 2015 and I am not deterred, as before, first opinions can be misleading

and I was excited to see what was in store second time around. In fact my

visits to PDD are becoming some of the most insightful experiences into art I

have ever had at an exhibition. This post reflects on some of those thoughts.

People should not be afraid to not understand art. I

think the image of authority projected by the galleries we place art in can

often dictate otherwise and there is a pressure or intimidation found in their

reverend silence and cathedral-like viewing spaces that fills people with a

sense of the unknown. I don’t think this is the fault of gallery spaces who go

to great lengths to ensure their buildings are as welcoming, user-friendly and

accessible as possible and it is a double-edged sword, galleries need to be

authoritative to give the work a kind-of cultural backing or approval that

gives conviction that, for example, this sheet of gold leaf on the floor is

‘art’. However I do not see any of this as a bad thing and think it is as

important to not know, expect the unexpected as much as it is to-know something. With art particularly

the complexity of each individual piece and ways in which meaning is constantly

shifting over time can mean that no one could ever claim to understand it all,

often not even the artist. On that note the introduction to the exhibition at

PDD states, “Each of the objects and

works of art (around 120) presented in the exhibition “Slip of the Tongue” seem

to partake in this idea that the activity of the artist is aimed at the

preservation and afterlife of objects rather than of their interpretation.”

Equally it would be wrong to assume that our soul engagement

or pleasure from art should be in attempting to understand/interpret it. Asking

what a stone axe head in a lump of clay is all about is a perfectly reasonable

question, but may actually have nothing to do with arts knowledge or experience

brought to the work by the viewer, but highlights that there must be something

intriguing or something possibly worth knowing about the art work. Conversely,

when I find myself in an exhibition asking myself what various works are about,

I then ask ‘why/what is it about the work I’m looking at that makes me

interested in it?’ In the case of our axe head I was initially attracted, of

course, because it featured a tool and there was something totemic-like or

primal about the way in which it was quite ‘simply’ stuck in the top of the

clay block that aroused suspicion. I wanted to know why the clay had been kept

in its clear shrink wrap casing as to being left to dry and whether this made

it, due to the condensation formed under the wrap a bit like a ‘breathing

sculpture’. It raised connections in the art history part of my knowledge of

Arte Povera, the ready-made as well as something more tribal or ancient. Even

without this assumed knowledge I think people would pick up on the clues in the

work but admittedly it requires more effort than some work. The work is part of

a series in this exhibition by French artist, Hubert Duprat. Titled ‘Volos’ it

is in fact named after the Greek island where in an archaeology museum a pre-Cycladic polished axe head replaces a

human head in a terracotta sculpture of

a human chest. The specifics of this may have taken some deducing or would

require knowledge of pre-Cyladic sculpture, but the essential ideas of

something ancient, and a breathing or flesh-like form could be read by most.

|

| Nairy Baghramian 'Retainer' (2013) Cast aluminium, silicon, polycarbonate, chromed metal, rubber. |

Despite its more demanding nature ‘Slip of the Tongue’ is

one of the more digestible exhibitions in this year’s Biennale in which Danish

artist, Danh Vo curates. Featuring some 39 artists from throughout art history;

mediæval miniaturists, Rodin, Picasso, Francesco Lo Savio, Carol Rama, Paul

Thek, Nancy Spero and Lee Lozano, Marcel Broodthaers, Hubert Duprat, Elmgreen

and Dragset to Fischli and Weiss it is still pretty sizable but in true Punta

Della Dogana style the works featured are at times difficult to spot given, at

times vast quantities of space to single works of art. Art Tourists expecting a

similar Biennale style art binge will relate to its ‘bit pretentious’

reputation as was my similar false judgement from two years ago. However in

contrast to the relentlessness and scale of the Biennale central exhibition

itself, PDD stands out for demonstrating that by giving artwork more space

(irrespective of its scale) it forces us to consider/notice it more. This is an

exhibition that rewards thoughtful interpretation for those who take the time

to look for it.

Baghramian also has two other works in the show, one of

which the title piece for the exhibition, ‘Slip of the tongue’ (continuing the

mouth theme). The work itself a combination of epoxy, resin, polystyrene and

concrete series of phallus looking sculptures which are meant to be more

tongue-like but in their uncertainty convey the idea of Freudian-slips and

stumbles of language and how it shapes our identity.

|

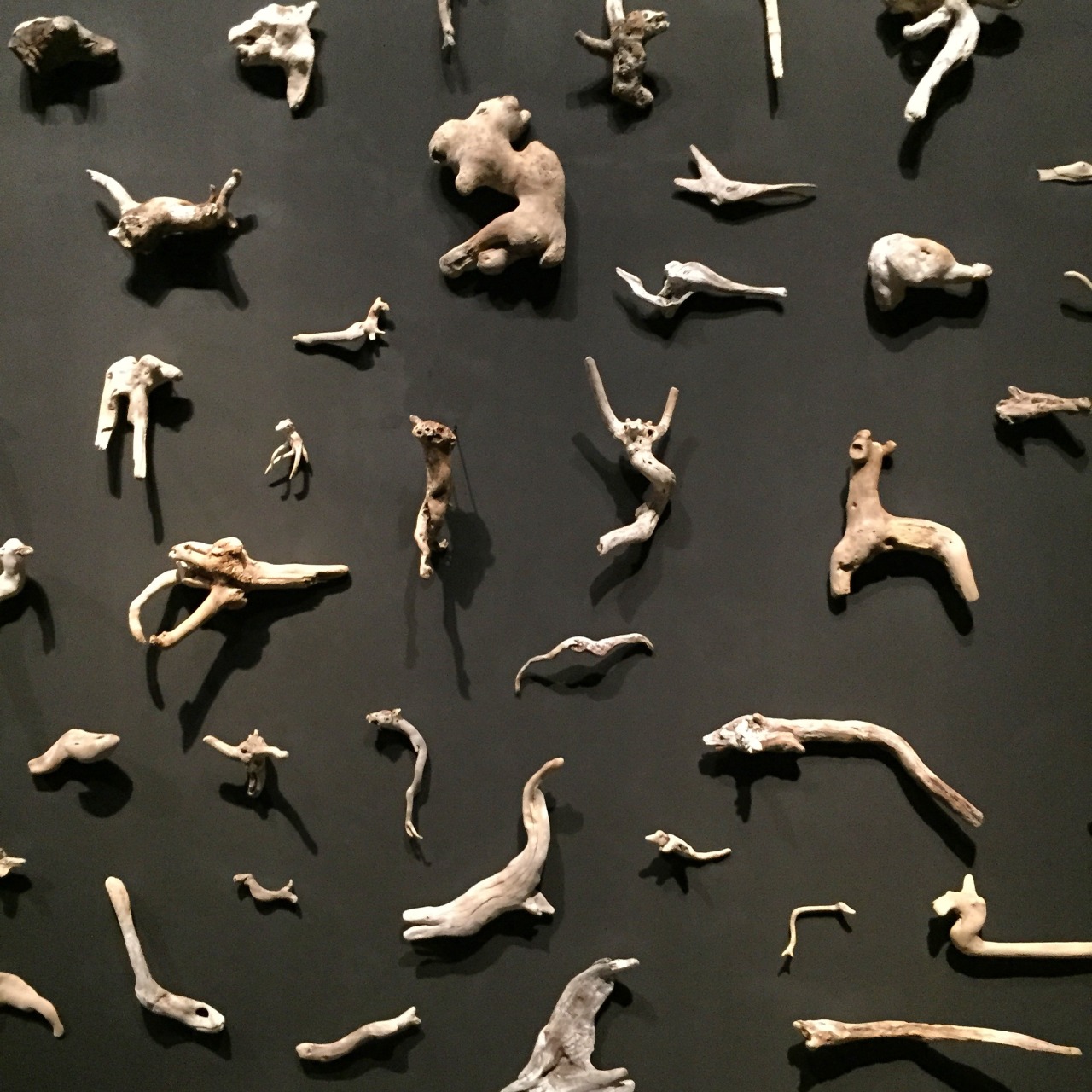

| Danh Vo 'We the People' Detail (2011-2013) Copper. |

In relation to the curator Danh Vo’s work the theme of

the broken and the mended, the beautiful and the delicate is referred to not

only in the artists he has selected but also his own practice which in some

cases combines fragments of classical sculpture with modern-abstract concrete

or wooden forms that both appear to hold-together and prop-up the original

sculpture and interfere with it at the same time. In Vo’s sculpture, ‘We the

People’ a set of giant broken and joined chain-links, is derived from a

painting showing a cross-section inside the Statue of Liberty by Martin Wong (also

in the exhibition). The links also refer to a piece Vo did about the Statue of

Liberty in New York five years earlier. The idea of making links and literally

depicting them is woven throughout the exhibition so that the work can be read

both individually and then a second time in relation to the work surrounding it.

|

| Danh Vo 'Untitled' (2015) Gold, cardboard, various iron and farm tools. |

Where this particular exhibition also challenges expectations is in that it has been curated by an artist. Whether it is perhaps because ‘artist as curator’ is more intuitively visually aware than a curator is, I don’t know but there could be argument in saying that this exhibition overall feels far more cohesive and more reflective of Vo’s practcice in its selection of works than that of the theme-based grouping of the Biennale ‘All the World’s Futures’ curated by Okwui Enwezor. Even down to the presenting of work aesthetically together is well thought-out with similar neutral tones, sepia hues and scales and sizes that vary from the elegantly small to the ambitiously large. From the late 19th century chandelier from the ballroom of the former Hotel Majestic in Paris which functioned as the headquarters for the German military in WWII to Sigmar Polke’s potato house and Andres Serrano’s ‘Piss Christ’ there is a LOT of art in this exhibition that begs to be thought about and how it talks to the other pieces that surround it paints a complex set of ideas around identity and biographical links to Vo’s mixed heritage of being a Vietnamese-born Danish artist that I’m still left unravelling weeks after having seen it!

Assisted in this plight visitors are burdened with what is an almost alarmingly comprehensive accompanying twenty-three page document which I think reads better as more of a catalogue to read after the exhibition rather than during. Tip; never find yourself reading the text in the gallery longer than you are ‘reading’ the work itself.

|

| Lee Lozano 'No Title' (1964) Graphite on paper. 36.5 x 46.5 x 2.5cm. |

The juxtaposition of

works throughout history, such as a Picasso next to a Lee

Lozano is another example of two artists whose work may have never been

seen together; Picasso amassed his wealth as an artist during his lifetime,

Lozano famously rejecting the idea of being an artist forcibly removing herself

from the art world in ‘dropout piece’ in the late 60’s. Politically and

historically they are two completely different artists, so in one way it is joyously rebellious

to put them side-by-side but visually it also allows us to compare their work

as paintings and celebrate the differences/similarities within the work. This

exhibition does feel a little like a Lozano retrospective and for me

personally, the real gem was seeing several of her ‘tool’ inspired drawings

from the 60’s. Compared to the similarly sexualised, intense drawings/prints of

Jim Dine (who was also working at same time as Lozano in America) very few

people have heard of her. This is in part due to her self-inflicted infamy of

wanting to disappear from the art world, but I think her drawings have so much

to offer as being the female reaction to what are traditionally very masculine

and at times phallic-looking objects. As drawings they aren’t very detailed or

refined, but they are very aggressive, dark, imposing and direct responses to

these objects that are openly sexualised and confrontational. In their

expressiveness and exaggeration they also remind me of Philip Guston’s drawings and although I did not spot it they have also been likened to Claes Oldenburg's sculpture drawings of enlarged or distorted common-place objects .

Watch this space as a more detailed post on Lozano is worthy an imminently due on this blog!

|

Lee Lozano 'No Title' (1964) Graphite on paper. x4

|

Overall this exhibition does draw attention to some of the treachery and misleading nature of language as well as challenging the purpose of art objects once they have finished being created. Art undergoing an existential crisis, 'what does art 'do' once it has been created?' It is one of the most concept riddled shows I have ever seen and I think the fact that I have struggled to summarize it succinctly only proves just how it defies simple explanation, but in doing so is also incredibly rich and rewarding. You’ll leave perhaps more confused than when you came in and that is a good place to start. What a difference two years can make!