The Venice Biennale is on until 26th November 2017, for further info visit: http://www.labiennale.org/en/Home.html

Britain – Phyllida Barlow ‘Folly’

It is difficult not to smile when first encountering Barlow’s work; colourful, larger than life, every piece installed within each space in a different way. I first saw Barlow’s work on a scale such as this at Hauser and Wirth in Bruton when it first opened in 2014. Her treatment of the British pavilion does not disappoint, columns in the central disrupt how viewers negotiate the room, followed by wracks of stained cloth, more tubes, blobs infiltrate the space outside and stacked boulder-like fabrications make up this ambitious and playful offering from the British artist now in her 70s. That play soon becomes more threatening however, as viewers have to squeeze past and lean around the gallery rooms, forced to alter their route by the sheer scale of some of these pieces and that they often occupy the walls, leaning outwards, other times suspended or simply plonked as a giant mod-rock clad obstruction. There is a lot of recycling and use of cheap readily available materials in her work that makes it feel exciting and accessible in the way she sees potential and use in such everyday things. If shape, form, colour, texture, volume are some of the ways we aesthetically perceive sculpture then Folly is an excellent example of what sculpture can offer.

In what looks like a retrospective of the Romanian artist’s work since the 1960s, Geta Brătescu’s drawings, collages, engravings, tapestries, objects, photographs and experimental film are displayed in the Romanian Pavillion at the Giardini. Spanning themes of ‘the studio’ and ‘space within-it’ along with reflections on female subjectivity; there is rather a lot to see. She studied both art and literature, evident in references of both in her work, one example being a series of drawings based on Faust. “In Brătescu’s practice the real, physical space meshes with the inner, intimate space and becomes part of the sphere of art....exploring phenomenology –her own hands...tension between the representational and non representational.” It made me think of outsider art in the way that it felt so personal, its quantity the product of obsession –this is a person finding things out about themselves and their context through making and doing on a prolific scale. I thought the hand drawings were exquisite and admired their difference to the loser, more expressive drawings. That duality interests me as it is something I am often at conflict with in my own work.

“Weinstein critically explores the mythological and Romantic images of Zionism embedded in Israel’s collective memory. The project reflects his fascination with the desire to stop time, with potential forms of construction, destruction, progress and devastation.” Mould and coffee are used to suggest the passing of time, allegory or a post-apocalyptic vision of Israel. ‘Jezreel Valley in the dark’ [pictured] consists of puzzle-shaped agricultural plots filled with coffee dregs that gradually grow mould at different rates. The smell that greats you isn’t very pleasant, nor probably is the realisation that it is mould all over the walls and floor, but for me I love the idea of having a changing installation at different stages of decay and where else can you view it and critique it in the context of being ‘art’. Here the natural process of the mould decaying is used to represent political or urban decay, the sprawl of time and how mould, like urban generation/degeneration can spread.

John Waters – Study Art [For Breeding or Bounty]

You’ve got to love a super kitsch; pop art style sign about studying art if you’re an artist don’t you? I certainly do and Waters’s series of ‘Study Art’ signs take his own intentions and turns language into a double meaning of a consumerist nature. Known for his film directing, (‘Pink Flamingos’) Waters, I learn, was once described by William S Burroughs as, ‘the Pope of bad Taste’. I like him even more! Deconstructing the clichés of the politically correct he is as debatably offensive as he is Duchampian-ly witty. If anything the humour of these pieces reminded me that it is important to not always [if at all] take art too seriously. Especially those who study art, these signs should be made available within every art department!

Republic of Korea – Lee Wan ‘Proper Time’

“Over 600 clocks engraved with the names, birthdates, nationalities and occupations of individuals interviewed from around the world. Each clock moves at a different rate that is determined by the amount of time the individual must work in order to afford a meal.” A lot of the Biennale feels like spectacle; which piece will be the biggest, most outrageous, most ambitious, most photogenic, most political or get its participants to do the strangest things? It is hugely competitive, with every work, every pavilion asking for everyone’s time to engage, therefore it is quite hard to determine whether one is interested in a work for genuine reasons or whether it all becomes a bit throw-away or commercialised. Lee Wan’s ‘Proper Time’ is one piece in a two-man exhibition in the Republic of Korea pavilion. The way in which you approach this work is by having to duck under and through a very low doorway into a white-walled room filled with the sound of ticking clocks. It is intentionally humbling, having to almost bow in order to enter this space; a sign of respect perhaps to the people whose time is being exhibited. The speed of the care-worker’s clock from Britain significantly slower than that of the hotelier in Abu Dhabi, though quicker than that of the cobbler from Budapest; these kinds of comparisons intentional in what becomes a vast visual representation displaying the scale of global inequality. It is fitting too that it is a part of an exhibition as a whole that explores themes of cultural identity.

Argentina –

Claudia Fontes ‘The Horse Problem’

There is no problem in ‘The Horse Problem, well at least

not one I can see, unless of course the problem is that this horse sculpture is

inexplicably huge! The idea behind the creation of the work was to present “...the relationship between man and his

horse which is the basis for the nation’s founding myth....the animal kept

captive in a prison [the Arsenale] built by its own motive power.” The

artist Claudia Fontes speaks of the use of horses to forge, plough and build.

That relationship she explains led to the building of borders and territories

that we now challenge and cause many self-inflicted problems in how people and

the land live together. It is a timely concept and one that current writer’s

such as Ulrich Raluff are exploring in his book, ‘Farewell to the Horse’ though

I am unsure if I would get much of that impression from the work itself it has

certainly ignited my interest in finding out more.Andora – Eve Ariza ‘Murmuri’ (Murmur)

Are they bowls? Are they mouths? Are they something other? However you see it, there are an awful lot of them in the Andora pavilion. Each one made in clay corresponding to different human skin tones, formed into the shape of a bowl as a symbol of, ‘the first container of truth’ they are meant as an offering of unity between languages. Each bowl becoming a listening vessel from which to hear the vibrations and subtle murmurings amidst the hustle and bustle of the Biennale. It is beautifully simple, the moulded bowls also form mouths and the ease in which meaning can be gleaned from this work was refreshing.

Republic of Azerbaijan – Elvin Nabizade

As part of the exhibition, ‘Under One Sun’ Azerbaijan hopes to present, the polychromi of culture in their country, “from its origins and traditional forms up to its different present manifestations”. There were several well executed immersive video installations within this exhibition but for me personally I could not resist the visual joy of seeing beautiful instruments suspended in sphere and arching forms from the ceiling.

Japan – Takahiro Iwasaki ‘Turned Upside Down, It’s a Forest’

Stacks of arranged books on a table become a representation of a mountain and skyscrapers. A citadel from which delicate threads of cotton from towels become steel towers, cranes and oilrigs. These are the fine crafting of Takahiro Iwasaki who uses everyday objects to make small interventions that signify both traditional and new landscapes in Japanese culture; from large mountains to chemical plants that stand along Hiroshima’s coast to a shrine built above the sea. They are playful yet superbly handcrafted, quietly commanding attention not for their scale but for their subtlety.

Italy – Giorgio Andreotta Calo ‘Untitled (The End of the World)’*

Andreotta Calo goes where Richard Wilson has previously gone with what, for the sake of argument is much larger, but visually very similar version of 20:50 that uses water as its reflective surface rather than oil. Despite the enormous space it occupies in the Italian pavilion it is just one artwork in the overall exhibition ‘The Magical World’ featuring three artists whose work we are told, shares, “...transformative power of the imagination and an interest in magic...” The surprise with this particular piece comes from first experiencing it from underneath; the viewer enters the installation to what appears to be a low dark ceiling suspended in place by a forest of metal scaffolding poles. As you traverse through this space you eventually come to a set of steep metal stairs leading upwards. The view at the top is initially disappointing as it is confusing; the stairs hit a brick wall. Nothing special about it; it isn’t until you turn-around that the trick is revealed. What was a ceiling held up by scaffolding was in fact a floor for a very, very large pool of water. This water reflects the architectural beams of the Arsenale pavilion playing with our sense of balance and creating another illusion. All three artists in this exhibition made intriguing work, the premise that, “...magic is not an escape into the depths of irrationality, but rather a new way of experiencing reality.” Of all the concepts in this year’s Biennale this was one that I thought was a refreshing change from the otherwise largely political agenda and I think it is important to remember in times as politically fraught as these of other forms of experiencing the world, a little magic maybe can go a long way.

New Zealand – Lisa Reihana ‘Emissaries’

In a panoramic, partly filmed, partly animated video projection ‘in Pursuit of Venus’ Māori and Pacific perspectives are shown in a re-imagining of the wallpaper, ‘Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique’ that, in 1769 referenced Pacific voyages of James Cook. It depicts real and invented narratives of cartographic and scientific exploration which happen simultaneously and on a scrolling loop from right to left so as to appear as life-size, moving wallpaper. For its use of animation mixed with filming it was distinctly memorable and along with its wit in showing a different perspective in a visually creative way.

Mexico – Carlos Amorales ‘Life in the Folds’*

“From abstract paper cut-outs [Carlos Amorales] created an illegible alphabet, which evolved into a series of ceramic wind instruments –ocarinas- producing a particular sound for each letter.” Viewing the Mexican pavilion felt like an experience in trying to decipher and understand something. Upon entering the first thing one sees is a dozen flat white, table-like surfaces with hundreds of black ocarinas laid out systematically. Without having read anything it was a real mystery to solve. How we understand language and how it is constructed is exactly the point of Amorales’s work and a visual language is perhaps no different in the way in which we attempt to interpret and ‘make sense’ of things. The ocarinas here represent an abstract language, visually they looked like shapes, symbols or birds to me, but further into the exhibition a film depicting them being played turns the typographical into the phonetic. I thought how the work in this exhibition was displayed was successful to interpreting its meaning, it felt museum-like and I enjoyed the challenge of it.

Tunisia – ‘The Absence of Paths’*

Set across three one-man sized booths in the Arsenale and across Venice visitors are invited to participate in registering for their very own Freesa; a protest travel document whose recipients ‘effectively endorse a philosophy of universal freedom of movement’. Part performance, part protest the work ‘The Absence of Paths’ creatively engages with the debate around migration. The passport sized pamphlet visitors are given articulates the idea behind the work very succinctly, “The world over, human migration –once a symbol for our continued social evolution –is facing headwinds from populist nationalistic movements. Diverse rhetoric centred on the building of walls and policing of borders is worryingly translating into action and is considered normal.” I thought this was a really effective idea and powerful way to engage people’s interest. Everyone who participates in the performance at the Biennale leaves their name and email address, making it a great case for unity and understanding given much of current world events.

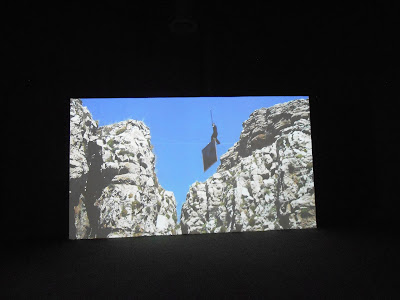

Taus Makhacheva ‘Tightrope’ 2015

In what was possibly one of my favourite video works from this year’s Biennale, Russian-Dagestani artist, Taus Makhacheva films a performance by Rasul Abakarov (descendant of a famous tightrope dynasty) “carry sixty-one art works copied from the museum of Dagestan between two mountains, from open air to a black structure reminiscent of museum storage.” At whatever point you encounter this film during its play, there is something very mesmerising about the task of which is unfurling before your eyes. Maybe it is the sense of danger and suspense from traversing the tightrope whilst carrying often large precariously balanced paintings or maybe it is the repetition of watching this activity play-out a dozen or so times that makes it so watchable. Will he drop one of the paintings [I hope not]? The viewer is compelled to watch and see. The film is also a curious way of viewing art works, the paintings suspended or carried move from one side of the mountain to the other giving us a panning view of each one as it travels by set against the stunning backdrop of the mountain range. It is as pleasing as it is unusual and subtly suggests how context is significant in how we view artworks. Once across they are safely and carefully stored, the pieces contained a comment on how museums deal with their storage and never exhibited art works. Politically Makhacheva’s dual heritage of being both Russian and Dagestani prohibits her to explore themes of how the West challenges invisible heritage, using elements in her work from both tradition and the present.

“The backdrop of

global protest against the oppression of women, which saw millions around the

world take to the streets earlier this year, “has made this work feel more

powerful, definitely”, said Cole...But as well as commenting on the wider

issues faced by women around the world today, the piece also comes from a

deeply personal place for Cole. Her grandmother was a child bride, married off

at 11 and gave birth at age 12. Cole also grew up in Israel and served her

mandatory time in the military, where sexual assault has long been an issue

swept under the carpet...”

I thought the context of the house or home was a meaningfully loaded place in which to show these works, the everyday domesticity of it and its familiarity took the understanding of the work outside of the gallery, which often feels very detached and put it into our real life.

Ibrahim Mahama –Ghana 1901-2030, 2016

A wall of worn shoemaker boxes obstructs the largest room of the Palazzo Contarini Polignac as part of the Future Generation Art Prize. It isn’t obvious at first quite what they are and until you get close do you notice polishing brushes and buckles in amongst the boxes that begin to give away what their purpose once was. It is revealed that these are exchanged shoemaker boxes, exchanged for new ones by the artist whose other well known work includes cladding buildings in used jute sacks from Ghana to transport coffee, rice and charcoal. Mahama uses these everyday items of work as raw material with which it is, “…possible to disrupt and subvert the politics of spaces by granting them new forms, imposing new meanings upon them, or divesting them of their intended significance.” These low-grade materials of everyday use displayed here on mass create a visual awareness of the scale and plight of our reliance on the work of the many individuals within these industries. On one level it seems wrong that these objects of use should be displayed so as to be viewed on their visual aesthetic and beauty, but the significance that each one has been collected by exchanging it for something new makes the work far more socially engaged than it does purely on aesthetics.

Whilst most of the pictures

here are my own, the ones marked with a * have been sourced online via the

following sites: http://moussemagazine.it;

http://www.cultweek.com; http://www.e-flux.com; http://www.kurimanzutto.com/index.php/artists/carlos-amorales

Text in italics sourced from: VIVA ARTE VIVA Biennale Arte 2017 Short Guide, 2017 and https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/may/11/hot-under-the-collar-venice-biennale-artist-uses-27000-neckties-for-installation

No comments:

Post a Comment